Irresponsible Denial

April 12, 2023

The recent story about a group of University of Malta students being arrested for performing a by the book responsible disclosure over a security vulnerability in a popular mobile app used by students, FreeHour is shocking. Everyone I spoke to about it today was similarly shocked or speechless.

The Maltese police force have come across as heavy handed, trigger happy and ignorant, clearly unable to understand how this kind of situation should be addressed.

FreeHour, particularly their CEO Ciappara has revealed incompetence by running a business completely based around a mobile application that is meant to share data, yet clearly not doing so securely or understanding how there was no malicious intent involved from the students.

There are a lot of hot takes going around social media right now and many of them are right, however few are delving into the actual situation and seeing where things went wrong.

It is easy to misunderstand or overlook the nuance of the situation, so let’s start from the beginning.

Responsible Disclosure

What is responsible disclosure?

This is a standard method used within the Information Security (InfoSec) industry which lays out how a security researcher should approach an entity about a security vulnerability they discovered. It is meant to protect the interests of both parties, but most importantly the general wellbeing of the consumers involved.

Let us construct an example situation:

Jane is a security researcher. She investigates a mobile application she uses frequently and discovers that the application is leaking other people’s personal identifying information, such as their personal address, when it is not supposed to.

These kind of issues are usually the result of bugs or misconfigurations, whether by incompetence or by negligence.

Jane decides that, in the interest of the wellbeing of all the users of the mobile application, to contact the company and inform them of what she discovered, so that it can be fixed.

Working under the rules of responsible disclosure, Jane sends an email to the company informing them:

- Who she is

- What she discovered

- How to reproduce it

- The approximate time, date and IP Address that she had at the time of discovery

- A timeline about when she expects this to be resolved before she proceeds with public disclosure (the standard is 90 days)

In an ideal world, the company:

- Understands that Jane is not acting maliciously

- Acts as soon as possible to mitigate and resolve the issue

- Informs Jane that the issue has been resolved so that she can confirm that the issue has been resolved

- Prepares a plan for disclosing the potential data breach to their customers (under Article 33 of GDPR)

- Optionally offers compensation to Jane for her services

The idea of offering compensation is that the payout to a security researcher would always be less than the:

- Cost of potential litigation in the case of a severe data breach

- Material cost of loss of business or abuse of systems by malicious actors

- Reputational damage suffered by the business

I state that it is optional because there is no legal requirement for a bug bounty to exist. It exists because it is more profitable to have one than to not have one.

Why set a deadline for public disclosure though?: This is a measure to avoid companies from passing the buck or outright ignoring the issue. Remember that the aim here is safeguard the wellbeing of consumers, not to pretend that everything is fine when in reality it is not.

Doesn’t a company have security experts to stop this from happening in the first place?: In my experience, most do not. Security is sometimes referred to as an “unwritten requirement”. We obviously want our systems to “be secure”, but security is not a single action or characteristic, it is an ongoing mindset and investment.

Some companies will pay for directed penetration testing (or pentests), either because they want to avoid the potential damage mentioned above or because of complaince reasons. The hard cold truth is that most companies just do not invest time and money into security.

Imagine a plumber had to come to your house and offer to ensure all your plumbing is working for 500 Euro. After you paid them 500 Euro, they come back and say, its all OK! If you do not appreciate the potential downsides of having shitty (excuse the pun) plumbing, then it is easy to feel ripped off by the plumber.

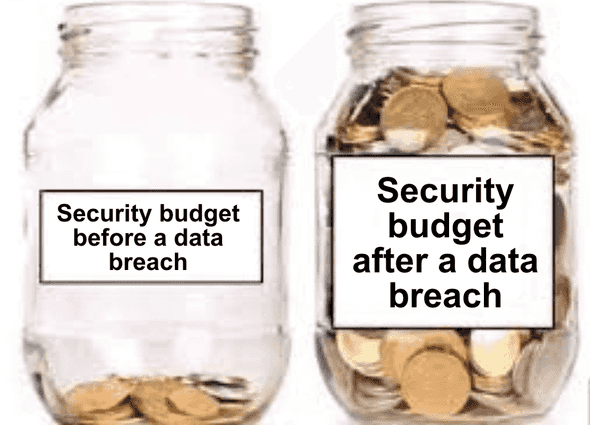

This meme sums it up pretty easily:

Ideally companies always set out and make their responsible disclosure policy clear and easy to find on their website. A great example of one is this page by the European Central Bank. It outlines very clearly:

- What the security researcher is expected to do

- What the security researcher can expect from the ECB

- How to inform the ECB and what to include

- Which vulnerabilities are considered in scope and which are not

- That they do not offer monetary return for any successfully reported vulnerability

This way expectations are managed very well for everyone involved.

An alternative example is the Vulnerability Reward Program by Google/Alphabet. It includes a table stating the potential payout of successful disclosures. The more impactful the issue, the more money a security researcher can expect to earn.

Irresponsible Denial

The above example was the fairy tale ideal scenario. The reality of what happened to these students is unfortunately much worse.

The details in the article by Times of Malta are a bit obscured however from what we can glean, the vulnerability was one of those that you just can’t believe someone would allow to exist (I had found a similar kind of issue myself as detailed here). The amount of data one could extract was appalling, the kind that you sincelery hope that no one else has discovered it yet.

Quoting the article, the CEO of FreeHour claimed that “We are pleased to report that no user data was compromised and the vulnerability was addressed within 24 hours,”. As someone who has a little bit of experience in this field (compared to the clearly no experience that Ciappara has), this statement sounds blatantly false.

Quoting from the above linked ECB responsible disclosure policy, they request the following: the IP address(es) from which the security vulnerability was identified, together with the date and time of the discovery;. The reason they request this is that, without this information, you are categorically unable to tell whether the only request made for the data was made by the security researcher/s.

The article implies that the only response the students received after sending the email was when the police arrested them at home, meaning that the company did not do proper due diligence in determining whether the vulnerability had been exploited before its discovery by the students.

My only criticism of the students would have been to avoid being naive about how Malta works. Everyone knows that things get done by knowing people and by establishing personal relationships. Even in my own experience, I wrote how I was paranoid that someone at the company would not understand where I was coming from and instead I went through a trusted acquitance who could vouch for me, establishing a chain of trust first.

Sending a cold email, using the proper industry standard jargon, to someone who may or may not understand what you are saying or have someone available to them who can explain it, is dangerous. For all we know, the email came across as something along the lines of “if you don’t pay us a bug bounty, then we will tell everyone in 3 months time”. I however repeat: this does not excuse the appalling behaviour that they have been treated with.

The Law

One has to ask: if Ciappara did not know what responsible disclosure is or looks like (which honestly, I can forgive him for not knowing, because from what I understand, he is not a technical person), why didn’t the police know? How did no one in the Cyber Crime Unit, upon reviewing the email sent by the students, realise what was going on?

What is scary for these students is that they are being investigated under Article 337, which very ambiguously states it is illegal to access an application without being “duly authorised by an entitled person”..

Unfortunately this law has not aged well. In this case the system was clearly (mis-)configured to authorise everyone who asks it for the data.

This was not some fancy hack involving zero-days and social engineering whereby the students broke into a super secure system and made off with a treasure trove of data. This was the equivalent of leaving a cabinet of papers out on the street where anyone could open it and look inside.

Do not let the lack of visual element of how computers work and interact with each other make it feel like anything less. People who work in Software… we see the world differently than non-technical people. We understand what happens under the hood and we do not take things at face value, which is why these kind of vulnerabilities are able to be discovered.

The future

This incident has the risk of scaring off anyone who has even the slightest interest in InfoSec or Computing from a very rewarding career and professional life. It will discourage the proper reporting of security vulnerabilities, leaving everyone in Malta worse off.

Seeing the people doing the good work be severely and unfairly punished, while the commercial entities get away scot free is severly unnerving and damaging.

As with anything in Malta, we begin the process of learning when these major screw ups happen. Hopefully the calls for Good Samaritan laws for security researchers are heeded.

I am happy to answer questions (best reach me on LinkedIn) and provide follow up as more details of the case emerge.